$\newcommand{\Dt}{\Delta t}$

We take a look at the implicit or backward Euler integration scheme for computing numerical solutions of ordinary differential equations. We will go over the process of integrating using the backward Euler method and make comparisons to the more well known forward Euler method.

Numerical integration is extremely important when it comes to simulating real world physical systems. For robotic systems, we usually have a continuous time state dynamics that tells us how the system behaves upon the application of a certain control signal.

\begin{equation} \dot{x} = f(x, u) \end{equation}

Here $x$ is the state of the robot and $\dot{x}$ is its derivative that tells us how the state changes upon the application of the control input $u$. Let’s say that we know that the initial state of the robot is some $x(t_0)$. We now apply control inputs $u_0, \ldots, u_n$ at times $t_0, \ldots, t_n$. What is the state of the robot at time $t_n$?

\begin{equation} x(t_n) = \int_{t_0}^{t_n}\dot{x}dt = \int_{t_0}^{t_n}f(x, u)dt \end{equation}

This is not something we want to compute analytically, hence we use numerical methods to get an estimate of future states. As long as we know the function $f$, along with the applied control inputs $u$, we can integrate the system forward from an initial state $x_0:= x(t_0)$ to any desired future time. This allows us to simulate the system and see how the robot behaves.

To simplify things, from now on we ignore $u$ and use the dynamics equation of the form $\dot{x} = f(x)$. The state is now dynamically changing as a function of the current state.

Consider the state $x(t + \Delta t)$ at a small time increment $\Delta t$ after $t$. We can use Taylor expansion to expand this around $t$. If we only take the first order terms, we have:

\begin{equation} x(t + \Dt) \approx x(t) + \dot{x}[t + \Dt - t] = x(t) + \Dt f(x(t)) \end{equation}

This is the forward (or explicit) Euler integration scheme. Let’s say we know that at $t_0$, the state of the robot is $x(t_0)$. Then at $t=t_0+\Dt$, we can compute $x(t_0+\Dt)$ using the above equation as we know $x(t_0)$, $\Dt$ and the value of $f$ at $x(t_0)$.

We can repeat this procedure incrementally to compute $x(t_f)$ at an aribitrary final time $t_f$.

\begin{equation} x(t_0 + \Dt) = x(t_1) = x(t_0) + \Dt f(x(t_0))\ \end{equation} \begin{equation} x(t_1 + \Dt) = x(t_2) = x(t_1) + \Dt f(x(t_1)) \end{equation} \begin{equation} \vdots \end{equation} \begin{equation} x(t_{n-1} + \Dt) = x(t_n) = x(t_{n-1}) + \Dt f(x(t_{n-1})) \end{equation}

Until $t_n$ is equal to the required time $t_f$.

Note that because the equation is an approximation, it works better if done in small $\Dt$ increments. For large $\Dt$ values, the Taylor approximation deviates from the true value and the errors begin to accumulate in our $x(t)$ estimates.

Now, we take a look at an example. Consider the function:

\begin{equation} \dot{x} = -7x(t) \end{equation}

We can compute the analytical solution for this ODE:

\begin{equation} x(t) = 7x_0e^{-7t} \end{equation}

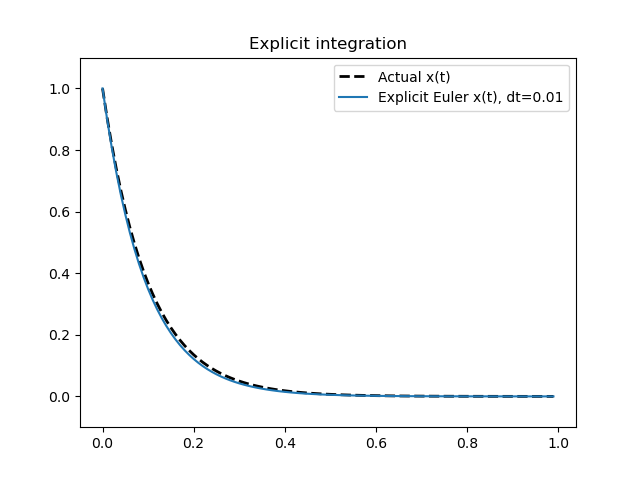

Where $x_0$ is the initial condition or initial state at time $t=0$. We can now plot the actual $x(t)$ values from the analytical solution, along with the numerical $x(t)$ values computed using forward Euler integration. We use an initial value $x_0 = 1$ and a $\Dt$ value of 0.01.

We can see how the numerical $x(t)$ values computed using explicit Euler integration are close to the analytical true values. As seen, explicit integration methods are usually easy to implement and compute.

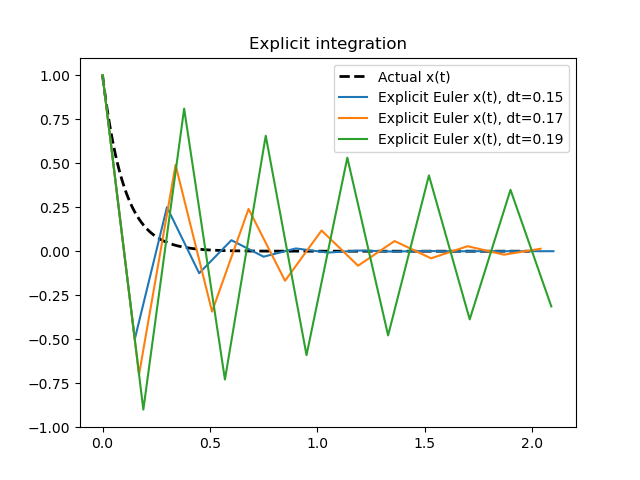

Now we get to the disadvantages of using such explicit integration methods. The equation we have at hand $\dot{x} = 7x(t)$ is an example of a stiff equation. Stiff equations become numerically unstable and explode for larger values of $\Dt$. Why is this of concern to us?

The size of $\Dt$ steps that we can take to find numerical solutions basically decides how many steps or computations are needed to compute the final state at time $t_f$. Smaller $\Dt$ means more accurate solutions, but also means that it takes a lot more steps to complete the integration procedure. In simulations, we wouldn’t want to be in a situation where we are required to use a small $\Dt$ value to guarantee numerical stability as this comes with a computational cost.

To check how the forward Euler scheme behaves for larger $\Dt$ values, we can plot similar graphs for different step values.

As we can see, the numerical solutions tend to be unstable. Implicit integration schemes are useful in such scenarios and provide numerically stable solutions, even for large step intervals.

Explicit integration schemes are usually of the form:

\begin{equation} x(t + \Dt) = g(x(t), \Dt) \end{equation}

Whereas implicit integration schemes are usually of the form:

\begin{equation} g(x(t), x(t + \Dt)) = 0 \end{equation}

The implicit Euler or backward Euler method follows a similar equation to the forward Euler:

\begin{equation} x(t + \Dt) = x(t) + \Dt f(x(t + \Dt)) \end{equation}

The difference being the dependence of $x(t + \Dt)$ on both sides of the equation. Naturally the question arises, if $x(t + \Dt)$ depends on the state derivative at $t + \Dt$, how do we compute it? One way of going about doing this is to use a Taylor approximation and expand $f(x(t + \Dt))$ about $x(t)$. A first order approximation would be accurate enough for this scheme.

Another way would be to treat this as a root-finding problem and use a root-finding algorithm. This finally brings us to the topic of the post, which is using the Newton-Raphson root-finding algorithm to solve the backward Euler update step. Writing the update step in the form of a function $g = 0$:

\begin{equation} x(t + \Dt) - x(t) - \Dt f(x(t + \Dt)) = 0 \end{equation}

We need to find the root of the equation, the variable here being $x(t + \Dt)$. The value of $x(t + \Dt)$ that sets this function to $0$ is the solution to the single update using the step size $\Dt$. We let $z:=x(t + \Dt)$.

\begin{equation} g(z) = z - x(t) - \Dt f(z) \end{equation}

To use the Newton-Raphson method, we start with an initial value $z_0$ that is close to the root solution and then iteratively update the solution using:

\begin{equation} z_n = z_{n-1} - \frac{g(z_{n-1})}{g’(z_{n-1})} \end{equation}

Where $g’(z) = \frac{dg}{dz}$. We iteratively repeat this procedure till $z_n$ converges. Numerically we would check if $|z_n - z_{n-1}| < \epsilon$ for some small $\epsilon$. For a given $z$, $x(t)$ and $\Dt$ value, we can compute $g(z)$ pretty easily. But how about $g’(z)$? For our specific case, we can compute it analytically as we know that $f(z) = -7z$.

\begin{equation} g’(z) = \frac{d(z - x(t) - \Dt f(z))}{dz} = \frac{d(z - x(t) + 7\Dt z)}{dz} = 1 + 7\Dt \end{equation}

What do we do in case it is not possible to compute an analytical solution? We can always approximate it with a numerical derivative:

\begin{equation} g’(z) \approx \frac{g(z + h) - g(h)}{h} \end{equation}

For a small chosen value of $h$. The last thing to clarify is how do we choose $z_0$, or the initial guess. For the Newton-Raphson method to work, our initial guess $z_0$ needs to be close to the actual solution. Luckily for us, we can use forward Euler to obtain this as we know that the forward Euler equation gives us a sufficiently close approximation to the final step solution.

\begin{equation} z_0 = x(t) + \Dt f(x(t)) \end{equation}

We can now continue with the Newton-Raphson procedure until we get a converged $z_n$ value such that $|z_n - z_{n-1}| < \epsilon$. This $z_n$ is now our solution to the single step update function. $z_n \approx x(t + \Dt)$.

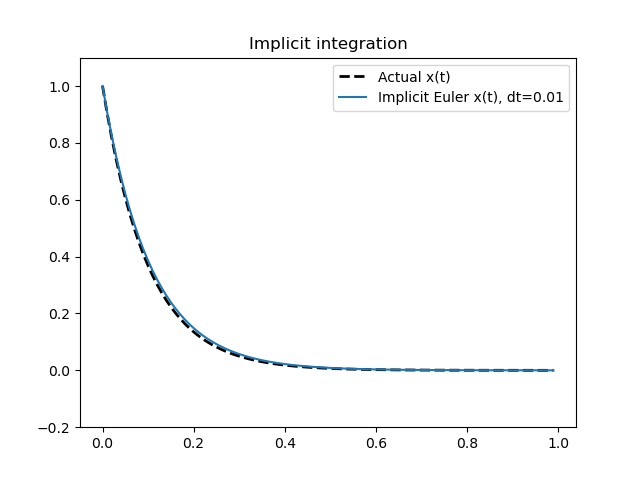

This procedure needs to be repeated for each step update. Clearly, this is more expensive than the simple forward Euler procedure for normal functions. But for stiff equations, and other complex dynamics functions with constraints, this could be cheaper than dealing with a small step size for large time intervals. We can plot the results of integration using this scheme for a small step size.

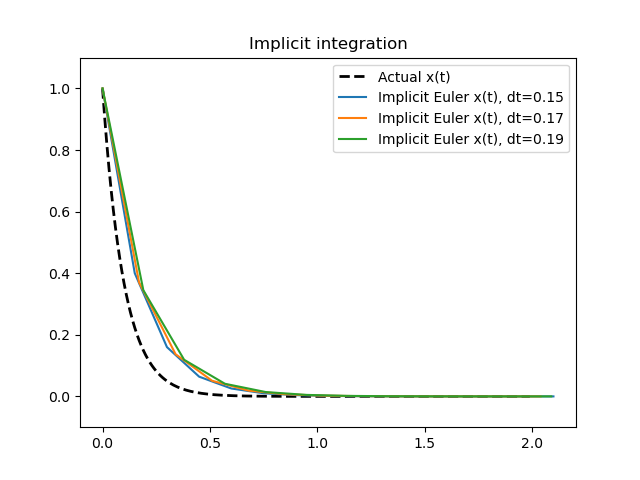

We get a very similar graph for a small $\Dt$ value. The biggest advantage of using such an implicit method is the fact that they are numerically more stable for larger $\Dt$ values. Plotting the same graph as we did earlier for larger step sizes, this time using the backward Euler method:

We can see that the numerical solution does not explode and remains stable, unlike the forward Euler case.